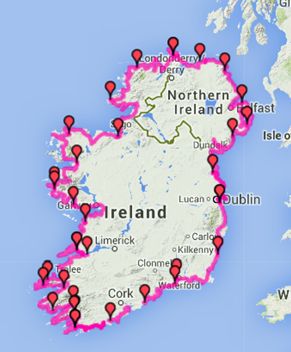

Well the Wild Ireland Tour is completed and I deliberately left writing an ‘epilogue’ for a short spell to take time to reflect on the month long odyssey. First of all, to present some of the statistics of the cycle:

Distance cycled – 3,200 km

Number of days cycled – 30

Elevation gained – 28,794 metres

Time in saddle – 128 hours

Calories used – 60,131

Approximate revolutions of pedals – 600,000

Punctures – 2

Falls from bike – 1 (don’t ask! – but no harm was done).

Before I left, I had set myself a wishlist of 10 species I wanted to see. By the end of the month, I had only seen four of the ten; Hummingbird Hawk-moth, Natterjack Toad, Dorest Heath and Twite. I had expected to fare better on this quest, but that I didn’t reinforces the fact that nature is not something that can (or should) be available on demand or, indeed, taken for granted. In one way I am pleased with this outcome, for it means that the Wild Ireland Tour has unfinished business that I should follow up on, and it provides the germ of a new adventure at a later date.

Since I finished, people have been asking me ‘what was the highlight of the Tour?’.This really isn’t a question I can answer, for the Tour was just a continuum of experiences, each different from the other. Certainly, some days were easier than others, but it would be wrong to categorise them superficially into highlights and low points. Some of the days that made for the most difficult cycling conditions, for example, gave me a greatest sense of personal satisfaction for being able to deal well with the conditions.

But there are two messages that I will take from this journey, one relates to the wonderful landscape we have and the other to lessons for nature conservation.

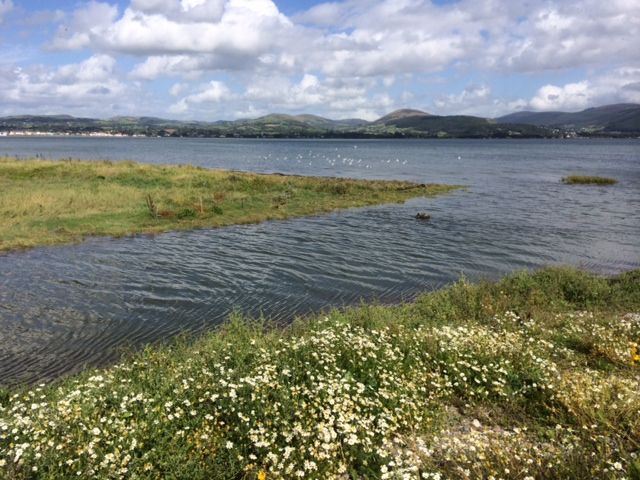

The Wild Ireland Tour took me through some of the most special landscapes and natural heritage sites in Europe. But no matter how stunning these areas are, without having people to share their knowledge and passion for their locality, and to serve as champions for nature, these place remain fairly sterile, inert areas. Yes, one can certainly be moved by the awesome power of waves breaking on the shore, or feast on the kaleidoscope of colours of a hillside, but it is only by seeing localities through the lenses of people who care, that places come alive and are imbued with character. Certainly investment in marketing and infrastructure is needed to unlock some of the value in our special landscape, but investment in people who can unlock the knowledge of the landscape is far more important if we are to gain the full benefits of our unique natural heritage. I don’t think this elemental precept has even begun to be appreciated.

I also realise that those of us who have an interest and appreciation of the rich biodiversity of the country are a fortunate lot. The differences that separates one grassland type from another, or one woodland habitat from the next, are subtle, nuanced differences. We are privileged to be able to view the countryside through this prism of detail, but we must understand that this is a world  invisible to many. If we are to build a greater constituency for nature conservation we have to look at ever more novel ways to communicate the value of biodiversity, and break down the barriers that have become established between conservationists and the rest of society. How we do this, I’m not too sure, but do it we must.

invisible to many. If we are to build a greater constituency for nature conservation we have to look at ever more novel ways to communicate the value of biodiversity, and break down the barriers that have become established between conservationists and the rest of society. How we do this, I’m not too sure, but do it we must.

The Wild Ireland Tour has been a fantastic experience. Bella and I enjoyed each other’s company for the entire month, an experience that we will both cherish. We met with some really inspiring people along the way, some of whom are working for conservation under difficult circumstances. I often heard it said that Ireland is a country of begrudgers; we found the exact opposite to be the case. People we approached to meet during the Tour could not have been more supportive or done more to help us along the way. Thank you all for your support, it is really appreciated.

There are two people I must thank for their special support. When first I broached the idea of cycling around Ireland to my boss, Gearoid O’Riain, Managing Director of Compass Informatics, he said two things; first, you’re mad, and second it was a great idea. (Actually he also said a third thing about the state of my backside, but that is not fit for sharing!). Without hesitation he agreed to sponsor the venture, sponsorship which made the Tour possible.

And of course, my wife Josephine for her huge support. In a weak moment last autumn, I first mooted my idea for the Wild Ireland Tour.  When I conveniently put the hare-brained scheme out of my mind, it was Josephine that kept reminding me of the idea, and took it as a given that the Tour would become a reality. And she was also understanding (well most of the time anyway!) of the need for me to spend many long hours training since the beginning of the year.

When I conveniently put the hare-brained scheme out of my mind, it was Josephine that kept reminding me of the idea, and took it as a given that the Tour would become a reality. And she was also understanding (well most of the time anyway!) of the need for me to spend many long hours training since the beginning of the year.

I hope the blog was worth following, and that it helped in some small measure to promote Ireland’s special biodiversity. This effort is finished and I must move on; I think the lawn needs cutting.