Here are some of the species that made the news from the year just gone.

Bermuda Petrel: In wildlife terms, this was certainly the find of the year. A Bermuda Petrel (also know as a Cahow), one of the world’s rarest birds was recorded in Irish waters for the first time in spring of this year. Niall Keogh (BirdWatch Ireland) was on board the research vessel the Celtic Voyager over the Porcupine Bank about 170 nautical miles north west of Slea Head when he made the amazing discovery of a Bermuda Petrel. This was the first sighting of this species in Irish waters, indeed for the entire North-east Atlantic. The species was thought extinct for over 300 years but was dramatically rediscovered in 1951, breeding on just four small islets off the Bermuda coast, with a tiny population of just 18 pairs. Since its rediscovery it has been the subject of a painstaking conservation programme with slow but steady success, and the world population is now estimated to be 108 breeding pairs. Seeing the Bermuda Petrel on a expedition in Irish waters was considered a million to one chance as this was the furthest sighting of the species from its breeding ground. The discovery by Niall Keogh, and confirmed by Ryan Wilson-Parr, made the birding news across the world, and made every birdwatcher in Ireland extremely envious of Niall’s discovery.

Read the Irish examiner article about the discovery.

Asian Clam: The invasive Asian Clam made the headlines in September when its discovery led to the closure of a stretch of the River Shannon to angling. Large populations of this highly invasive species were found along the hot water discharge from the ESB electricity generating station on the River Shannon at Lanesborough, Co. Longford. Inland Fisheries Ireland took the unprecedented step to close the river to angling as a rapid response measure in an attempt to stop its accidental spread on fishing equipment such as nets, rods, boats and clothing. The Asian Clam was first discovered in Ireland from the River Barrow at St. Mullin’s in 2010, and has since been found on the River Nore and at five sites on the River Shannon.

Read the Inland Fisheries Ireland’s press release.

Read article in Westmeath Independent.

Southern Cuckoo Bumblebee: there was great excitement when in June when a species of bumblebee not seen in Ireland for 88 years was rediscovered. The discovery of the Southern cuckoo bumblebee, thought extinct in Ireland, was made by Eddie Hill, a Gardener at St. Enda’s Park in Rathfarnham, Dublin. Eddie had begun monitoring of bee populations as part of the Data Centre’s Irish Bumblebee Monitoring Scheme and was astonished to make such a discovery in his first year.

Read the National Biodiversity Data Centre’s press release.

Read Irish Independent article.

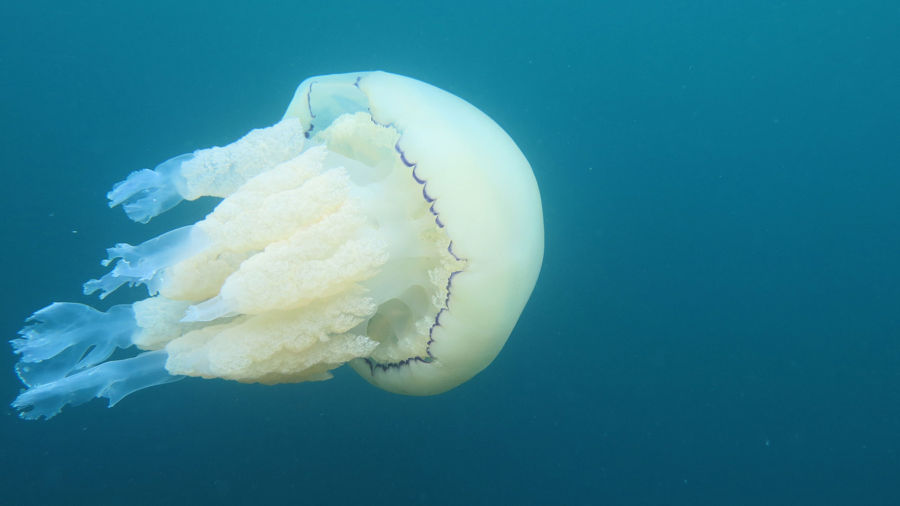

Lion’s Mane Jellyfish: Lion’s mane Jelly made the news in August, with reports that 17 were removed from Sandycove Beach. These large bell-shaped jellyfish have long tentacles which can cause severe stings to bathers. As a result, Dun Laoghaire Rathdown County Council erected warning signs at three beaches in South Dublin, Killiney, Sandycove and Seapoint, alerting bathers to the presence of jellyfish. This story followed hard on the heels of an earlier story of reports of Portuguese man o’ war, which strictly speaking isn’t a jellyfish, and barrel jellyfish being washed up on our shores. But according to jellyfish expert, Tom Doyle, there were no verified sightings of Portuguese man o’ war in Ireland in 2014, so the reports were in error. Being the silly season with regard to news, the jellyfish caused a bit of a media flurry at the time.

Read the first Irish Times story.

Read the second Irish Times story.

White-tailed Sea Eagle: Raptors were in the news quite a bit in 2014, mostly for all the wrong reasons. But there was a real feel good factor around the success of the White-tailed Sea Eagles breeding for the second year running at Mountshannon, Co. Tipperary. The local community has taken to the new residents, and a special viewing and information point was opened to cater for visitors to view these magnificent birds. The Mountshannon pairs was one of 14 breeding pairs established in Ireland in 2014, an increase of four on last year. Seven pairs laid eggs in 2014, with one chick at Mountshannon being the only fledged chick. The White-tailed Sea Eagle re-introduction programme began in 2007 in Killarney National Park and 100 birds released. The programme has suffered some setbacks, in particular with the mindless poisoning of at least 12 the birds. Thanks to the dedication of the Golden Eagle Trust, National Parks and Wildlife and the many volunteers, the White-tailed Sea Eagle project might just be on the cusp to great success.

Read more in the Irish Examiner article about the success to date.

Read more about the Mountshannon White-tailed Sea Eagles here.

Read the details form Golden Eagle Trust’s website

Pygmy Shrew: The Pygmy Shrew, one of the world’s smallest mammals, hit the news in June with claims that it is disappearing from parts of Ireland because of the impact of the newly arrived invasive Greater White-toothed Shrew. A team of researchers led by Allan McDevitt in UCD showed the Greater White-toothed Shrew was rapidly colonising the midlands of Ireland at an alarming rate of over 5km per year. Where they occur, they are likely to outcompete their smaller relation, and possibly leading to the local extinction of our native Pygmy Shrew. For a mammal that has lived in Ireland for thousands of years, this is a real shame.

Read the Irish Independent article.

Read article from the Anglo-Celt.

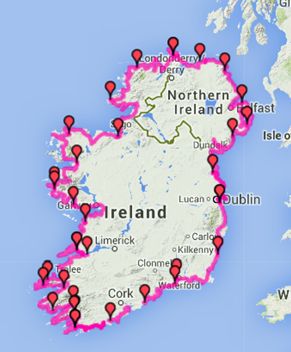

Japanese Kelp: September came the news that the invasive species Japanese Kelp, was discovered for the first time in the Republic of Ireland. Already known to occur at Carrickfergus Marina in Belfast Lough since 2012, it was confirmed to have spread to Carlingford Lough in the Republic of Ireland in September. Japanese Kelp is native to Japan, Korea and China, but has since spread to New Zealand, Australia, the United States and Europe. Within Europe it occurs in the United Kingdom, France, Spain and Italy. It is considered one of the worst 100 invasive species in the world. Japanese kelp is the latest in a large number of non-native and invasive species that have colonised our shores.

Read the National Biodiversity Data Centre’s species alert.

Read the Sunday Times article.

Waved fork-moss: In June, the Minister for Arts, Heritage & the Gaeltacht, Jimmy Deenihan, T.D. issued a press release announcing the discovery of a species of moss previously presumed extinct in Ireland. The rare moss Waved fork-moss was discovered in Clara Bog Nature Reserve by Dr. George Smith who stumbled upon it while preparing for a workshop at the site. The moss which is a specialist of raised bog habitat was thought extinct because of the large amount of raised bog destroyed in Ireland in the last century. Clara Bog Nature Reserve protects a 450ha raised bog, one of the best examples of this habitat in the world. Instead of cutting peat from these extra-ordinarily rare habitats, we should be cherishing them.

Read the Minister’s press release.

Seagulls: well what can I say? The impact of ‘seagulls’ was raised in the Seanad by Ned O’Sullivan, who wanted Dublin ‘…to introduce policies to limit seagull numbers and abate their noise levels and more aggressive behaviours’. Why? Because apparently inhabitants of Dublin were being kept awake ‘by seagulls screeching throughout the night. They are fighting, bickering and are raucous. They have caused sleep deprivation’. He also claims that ‘..youngsters have been attacked in parks and had their lunches snatched.’ Thus ensued a great deal of media coverage on the topic of seagulls, much of which it must be said ridiculed the concerns of the Senator.

Read Una Mullally’s pieces from the Irish Times.

Read the Irish Independent article.

Read the Irish Mirror article.

Read thejournal.ie’s take on it all.

Hen harrier: The hen harrier has been in the news on and off during the year, mostly for all the wrong reasons. Early in the year it was the threat to hen harriers from large scale wind farm development, then it moved to the issue of afforestation. Hen harriers and afforestation restrictions has become a hot political issue as farmers are ‘…not being properly compensated’ for the ‘restriction’ on their farming activities within Special Protection Areas (SPAs), according to the Irish Farmers Association. A new farming group, Irish Farmers with Designated Land, has been lobbying hard to have the restrictions on new afforestation within SPA weakened, as they claim the €7,500 per year payment proposed under the new GLAS+ scheme is inadequate ‘compensation’ for their ‘losses’. Their efforts seem to be paying off as Ireland South MEP Sean Kelly is now championing their cause, and Minister for State at the Department of Agriculture, Tom Hayes is in favour of allowing further afforestation within SPAs designated for hen harrier conservation. The controversy over hen harriers and afforestation has caused an impasse over designation of 90,000ha for SPAs, an impasse which the EU Commission claims needs to be resolved before Ireland’s Rural Development Plan can be finalised. Earlier this month, BirdWatch Ireland and the Irish Raptor Study Group issued a statement calling for the end of vilification of the Hen Harrier. It also claimed that the allowing further afforestation in SPAs would be ‘…an environmental disaster and have a devastating effect on the national hen harrier population’. No doubt, this issue will remain in the news for 2015.

Read conservation group’s call for end of vilification of hen harrier

Hen harrier row could delay government RDP package

Farmers seek end to ‘restrictive’ hen harrier legistation