Did you ever spare a thought for the jellyfish? I certainly haven’t, but there is far more to a jellyfish than meets the eye. Jellyfish have been quietly living their lives, roaming the great oceans of the world for at least 500 million years. They evolved during the Cambrian Explosion, a short period in the Earth’s history that saw a great flurry of evolutionary activity. While other organisms joined this evolutionary rat-race to go on to become dinosaurs and a myriad of other creatures, the jellyfish, happy with its lot, shunned evolution and retired to the peace and quiet of the high seas. This may, in part, be due to the fact that they are without brains, or at least brains as we typically think of them. Their bodies, of which more than 95% is water, comprise two basic layers of cells. One forms a loose network of nerves called the ‘nerve net’ which is considered the most basic of all nervous systems identified in multi-cellular organisms. This primitive system allows jellyfish to sense their environment, such as changes in water chemistry indicating food, light sensors to detect the presence of light, and balance sensors to let them know if they are facing up or down. Basic, but effective weaponry, which has allowed jellyfish to prosper down through the millennia.

It is a misconception that jellyfish just aimlessly sail the high seas at the whim of ocean currents and tides, for the manner in which certain species are geographical spread suggest they have some habitat preferences. Around the Irish coasts, for example, the barrel jellyfish each year forms enormous smacks (a ‘smack’ is the collective noun given to a group of jellyfish) off Rosslaire and Wexford Harbour, but is rarely seen elsewhere in such numbers. And the Lion’s Mane jellyfish seems to prefer the cooler waters off the coast of Dublin.

The knowledge of jellyfish around Irish coasts has increased in recent years thanks to research done by Tom Doyle, Damien Haberlin and colleagues at the Coastal Marine Research Centre at University College Cork, research that was spurred on by the apparent worldwide population explosion of jellyfish. It is thought that the removal of top level predators through over-fishing may have created conditions to allow jellyfish to flourish. Similarly, changes ascribed to climate change have also been implicated for this increase. There is no hard evidence to show that jellyfish have increased in any great numbers in Irish waters, however, the closure of beaches in Dublin in 2005 due to a Lion’s Mane jellyfish infestation, has raised the issue in the collective consciousness.

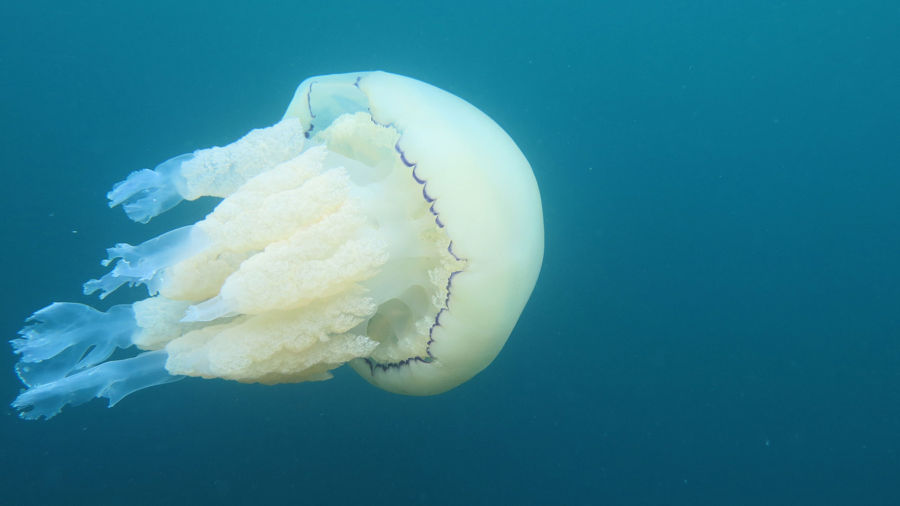

If your only encounter with a jellyfish is an unexpected eye-to-eye one when swimming, you could be forgiven for not being their greatest fan. Not all jellyfish are small unspectacular blobs of jelly, but they come in a variety of shapes and sizes. The Lion’s Mane is a majestic reddish-brown gelatinous bulk over 1 metre in diameter with masses of long tentacles. Also spectacular are the wonderfully coloured and shaped Compass and Blue Jellyfishes, both roughly the size of a dinner plate. The Barrel Jellyfish is a huge mass of solid ghost-white jelly. Tom Doyle and his colleagues found one specimen that was 80cm in diameters and weighted in at 35kg. Now that’s a lot of jelly(fish).

Then there are the other jelly-like creatures found around the Irish coast. The wonderfully named ‘Portuguese Man-O-War’ which has a Cornish pastie shaped balloon as a float. Riding the waves with the balloon above water, it somehow resembles an old warship at full sail. But the Portuguese Man-O-War is not a jellyfish, nor is it even a species. Rather it is a colony of creatures that work together to eke out a living, much in the same way that marine corals do; scientifically they are referred to as Siphonophorae and are related to jellyfish, corals and others. But as its name suggests, give the Portuguese Man-O-War a wide berth for its body and tentacles, which can extend for 50m, contain a serious sting. Portuguese Man-O-War made the news headlines in 2012 when some were found washed ashore in Waterford and Cork, but fortunately they normally live further south and only venture north when unusual weather conditions persist.

But there are many other, less spectacular Siphonophorae living in Irish waters, beautifully shaped jellyfish of varying sizes, each with its own delicate shape and function. And jellyfish do serve important functions; because of their sheer abundance they eat vast quantities of plankton, crustaceans and fish, and in return vast quantities of jellyfish are themselves preyed upon, thus fuelling the marine food web. And jellyfish can be quite the delicacy; the leatherback turtle apparently likes nothing better than to feast on jellyfish, and has been known to swim all the way from the Caribbean to Irish waters searching them out.

So next time you meet a jellyfish spare a thought for how they have done so well for themselves in this rat race of life on earth.