Today was earmarked as a rest day, but I thought it worth cycling the Malin Head circuit to experience it properly, and all the better as Emmett Johnston agreed to keep me company. Ostensibly this was to be about Basking Sharks, but quickly it became apparent that Emmett knows this area intimately and wanted to tell me all about it. We headed north-west towards Lagg beach, climbed to a vantage point overlooking Five Fingers bay, and dropped down to White Strand Bay, before rising again on our road to Malin Head. Emmett pointed out dune systems where different conservation priorities can become entwined. For example Chough like tightly grazed dune grasslands whereas the conservation of the dune flora probably does best with light grazing. He pointed out a small overgrown haggart beside a derelict house where a Corncrake had set up territory. It didn’t matter to me that I could neither see nor hear them, just knowing that there was a family of Corncrakes so close by was a thrill in itself. This was one of nine calling male Corncrakes in Malin Head this year which is up on previous years. The whole route out to Malin Head was just one special nature conservation story after another. Dunlin, richly vegetated hill slopes and verdant bog pools added to the experience.

Yet I get the impression that it frustrates Emmett that the local community living here can’t benefit more from their really special surroundings, surroundings that are to be found nowhere else in Europe. Rather than politicians trying to bring employment in the shape of Call Centres and the like to these wonderfully diverse natural areas, could employment opportunities based on those special natural resources not be found? After all, the people here are of the land and of the sea, it is what they know best and are best equipped to capitalise upon. The key is to find ways in which management of our unique natural heritage can be predicated on a reward’s system, rather than just becoming an additional burden on an already stressed socio-economic community.

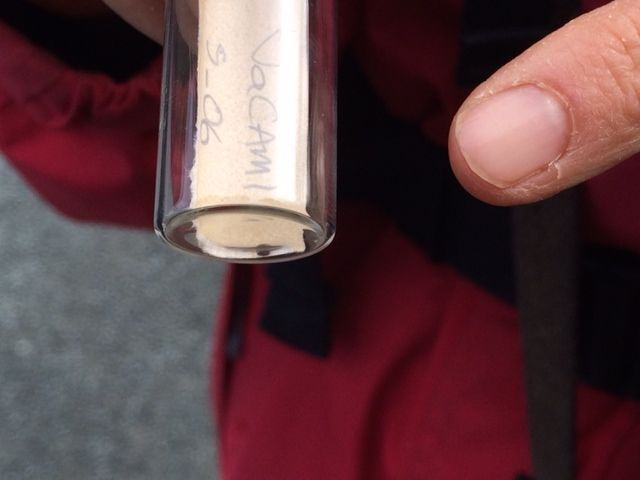

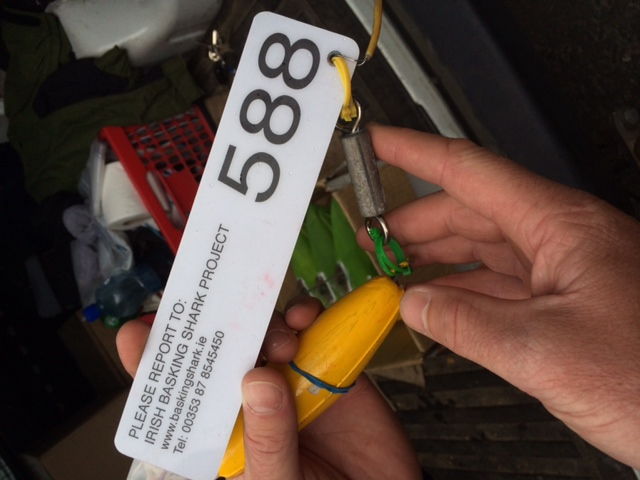

Emmett holds out hope that Basking Sharks might be one of the keys to the area’s survival, or even revival. For a long time no one paid much attention to Basking Sharks. The local crab and lobster fishermen in these areas were used to seeing congregations of Basking Sharks at certain times of the year, yet no interest was shown in these majestic creatures, as they were neither a conservation not a commercial fishing priority. Having his interest tweaked by Simon Berrow, Emmett set about finding out more about these animals and is doing really seminal research. He has tagged Basking Sharks to understand more about their movements, and working with colleagues, he attached short term video capsules to a small number of animals to observe their behaviour close up. He also engages with the fishermen to learn from them and to gain their support.

And he is finding out that Malin Head is of world importance for Basking Sharks, the world’s second largest fish. They pass Malin Head early in the summer in great numbers, not lingering but moving through at speed. At this time of year 1,000s pass through in the space of a few days; which if current global population estimates are to be believed would make the waters of Malin Head probably the most important route for Basking Sharks in the world. Later in the year, around this time, Basking Sharks return to these waters, but this time their movement is leisurely, with animals in no hurry to move on. Some animals have been seen in the area for weeks at a time. Many theories are advanced to account for this behaviour, but it is mere speculation at this stage. What I also found surprising is that Emmett tells me that the usual picture of a Basking Shark swimming slowly through the water, mouth-open hoovering up plankton, is only one aspect of their behaviour. Having completed a first sweep of a plankton swarm, they dart back at speed to the start of the swarm to begin over again. They also breach, apparently.

There is a fantastic story to be told about the Basking Sharks, and Emmett and some colleagues think that Malin Head is where that story should be told. They have developed plans for a Marine Ocean Centre adjacent to Malin Head, where research, local fishing and tourism interests could merge. Already two young students from the locality who have been bewitched by the Basking Shark work have gone on to study marine biology, which Emmett sees as a good sign. A great deal of work is still needed if this Marine Ocean Centre is to become a reality, but it is ambition and foresight like this that might just save special places like Malin Head.

As Bella and I sat with Emmett near Malin Head looking down onto the sea stacks and the ocean beyond, listening to the unfolding story of Basking Shark behaviour, it made me appreciate that there is such a wondrous natural world out there that we are still only beginning to understand and appreciate. I had earmarked Malin Head as the place I would see Basking Sharks on the Wild Ireland Tour, but in a strange way, I was kind of glad that the sea was too rough to see them, for it means that it will give me an excuse to come back again. And, I get the sense that this is one species that Bella might come back with me to see too.