Today I decided to put in a long day’s cycle and covered 165 km from Newcastle to Drogheda. The route had no significant climbs and a good road surface so though I would take advantage of that.

But I must have upset all four of the wind Gods at some stage for they are conspiring together to keep a healthy wind in my face, and changing daily for maximum effect.

The first part of the cycle took me along a beautiful road with Slieve Donard towering over me to my right and the wide expanse of Dundrum Bay to my left. At Rostrevor, a combination of lovely mixed woodlands and open scree on the western side of the mountains provides the village with a stunning backdrop. The Mourne Mountains are designated an ‘Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty’, a designation which we don’t have in the Republic. The designation doesn’t appear to have much teeth, but it is a beautifully positive way to promote a beautiful landscape. The Mournes have also been proposed as Northern Ireland’s first National Park, but progress on this appears to have stalled due to local resistance.

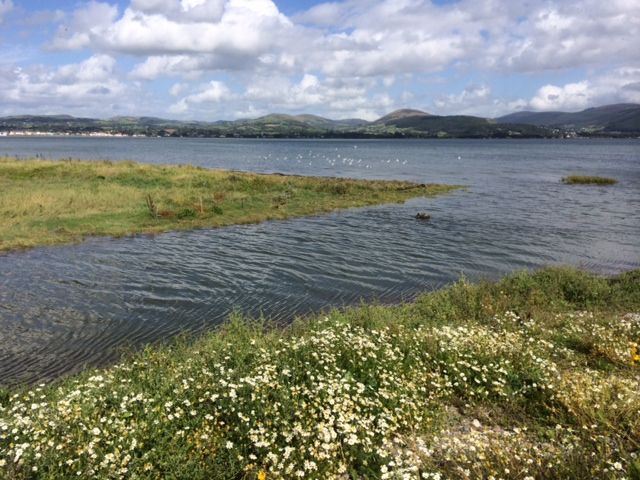

Carlingford Lough straddles the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic and is yet another of our bays of high conservation value. The northern side of the lough has extensive mudflats and salt marsh vegetation, valuable feeding ground for our migratory wildfowl. The southern shore is remarkably different, as it is more exposed to currents and onshore winds. It forms a narrow band of pebble, shingle and rocky shoreline, but equally important for the pebble and drift line habitats it supports. For these are rare habitats at the European level, and while they support sparse vegetation, the plants found there are specialised.

Plant typical of this drift shoreline, for example, include Sea Rocket, Sea Sandwort, Sea Spurge, Sea Mayweed and the rare and protected Oysterplant.

As I cycled along the southern shore at high tide, I spotted a small island of land above the tide line, used as a roost by Curlew, Redshank, Gowdits, Oystercather, Little Egret, Grey Heron and gulls. All were crammed in, orderly segregated by species to their allocated area – a lovely sight.

The final part of the cycle took me along the shore of Dundalk Bay. Although referred to as a bay, it has the characteristics more of an estuary with vast expanses of sand, mud and saltmarsh exposed at low tide. Thanks to the efforts of a large number of volunteers, the birdlife of the area is counted regularly each winter as part of the national Irish Wetland Birds Survey,

organised by BirdWatch Ireland and NPWS. This is a huge undertaking for it involves counting wetland birds at more than 600 wetland locations, inland and coastal, once each month from September to March. And what is more remarkable is that more than 80% of the counts are done by volunteer birdwatchers who give of their expertise and time freely. As a result of this effort, an accurate picture of the most important wetland sites in Ireland for birds is obtained, and any changes to populations from year to year are identified.

Dundalk Bay is of inordinate importance for wading birds as it supports well in excess of 40,000 waders each winter,

more than double the number that would qualify it as a site of International Importance. More than 12,000 Oystercatcher alone winter here. But surprisingly few wildfowl use the site in winter, despite seemly ideal feeding habitat. It seems that wildfowl find conditions elsewhere more to their liking.